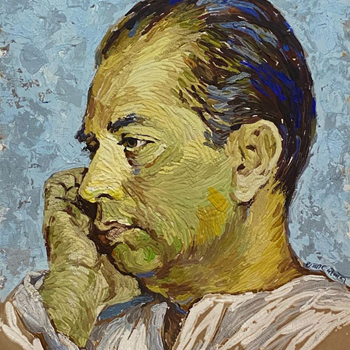

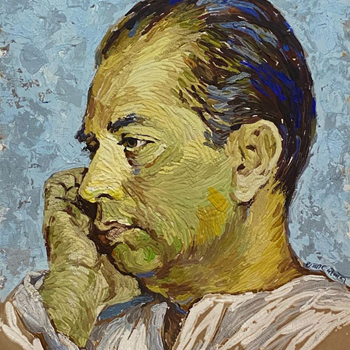

Legends on Legend

“With his very first film Udayer Pathe (Hamrahi in Hindi), Bimal Roy was able to sweep aside the cobwebs of the old tradition and introduce a realism and subtely that was wholly suited to the cinema. He was undoubtedly a pioneer. He reached his peak with a film that still reverberates in the minds of those who saw it when it was first made. I refer to Do Bigha Zamin, which remains one of the landmarks of Indian Cinema.”

If I were to evaluate Udayer Pathe ,I have to frankly admit Bimalda literally pulled out Bangla cinema from the dark abyss. Then came his Anjangarh. And what a phenomenal experience that was!

Most know him through his films, I know him from my heart and soul. What kind of cinema he created is not of particular significance to me…the kind of individual he was is of far greater importance.

I am saying all this after nearly fifty years since I first met him: Bimalda was a pioneer, a craftsman, a true artist, and a visionary:

The leading light of this era was Bimal Roy. He was the architect of its ideology and the pathfinder of its cinematic values. Bimal Roy was thus the central figure, the pioneer who inspired the cinema of the 1950s, its golden age. He did more than merely make the Bengali type of film in Bombay; he created his own methods of coping with the contrary demands of art and the box office, and stuck to them till the end, establishing an enduring model in the process.

The present might well be a surreal extension of Bimal Roy’s sombre view that nothing was going to get better. Are we then living in the mixture as before? Not at all – we have come a long way since the 1950s But I found the film with its almost unbearable bleakness disturbing also for its flashes of similarity to today’s India and it left me feeling uncomfortable about all that we have failed to deliver.

During his time, the Bombay film industry had people e Mehboob Khan on one side and film-makers like V. Shantaram on the other—these two were big names—and most people went to see their films not because there were stars in it but because it was Mehboob or a Shantaram film. The third big name was Bimal Roy.

In Do Bigha Zamin (1953), apart from the influence of Italian neo-realism in recording urban and rural poverty, there is a very clear link between the feudal system in rural India and the growth of the urban ghetto. Shambhu (Balraj Sahni) loses his ‘do bigha zamin’ because there has been no land reform taking place and the zamindari writ allows the thakur to grab his land illegally Eventually, at the end of the film, the land is auctioned and the plot ends up as industrial estate. Shambhu is left contemplating with a handful of dirt in his hand.

Bimal Roy’s approach was constructive. Unarguably, one of the greatest film directors, his legacy transcends the art of cinema to touch the collective consciousness of a society. At the same time, the larger aspect of his work did not alienate viewers. He moved and touched the inner being of the person who viewed his craft. His approach seems to be a collaborative one, that of inviting the participation of his audience to introspect and engineer a change in perspective.

All hell broke loose and Salilda was very tense when Gulzar suggested that he adapt a Bengali tune of Salilda in Hindi and Gulzar volunteered to throw in some words. Well, under the circumstances that seemed like the best option and when Bimalda came he liked what he heard but made it very clear that he realized that it was a last-minute adjustment. The song was ‘Ganga aye kahan se ganga Jaye kahan’. The biggest gain for me while doing Parineeta was discovering Bimal Roy and his films, especially the songs in them. These are changing times and it is a struggle today to convince directors on a good tune and many of the songs picturized never manage to scrape past the ear. Songs are slotted as ‘happy’ and ‘sad’, and recording labels hate ‘sad’ songs.

Yes, I miss Bimal Roy.

Bimal Roy’s choice of stories illustrates his deep compassion for and understanding of the plights of the underdog.

To me it was an education to work with him. In my formative year it was important to work with a director who lead you gently under the skin of the character. Today we have institutions, they teach cinema, acting etc. We did not have these in our times. We had instead directors like Bimal Roy. Add to this my own application as an actor. Take making Devdas. The question often while doing my role was ‘not to do’ than do anything.”

We did not use those labels. For me, it was a millennial film. That it was a state of being, a society we aspired to. We loved the millionaire’s daughter for falling in love with the leftist hero. And all’s well that ends radically well.

I first met him during the story session of Sujata at his office and he explained the important details of my role while the writers were narrating the story. I felt confident at once for he knew what he wanted and would see that I gave that in my portrayal.

On Bimalda’s set, each individual was engrossed in his work, as if he was a general on duty When it was time to shoot the scene, it seemed like an organized army unit awaiting their commander’s signal to launch into action. That particular scene at the kothi needed to be shot at one go. By the end of the scene, the zamindar stomped out of the room, but only after disentangling his foot from the grovelling peasant’s grip. The camera was carefully placed on the trolley, the plotted movements were complicated. Preparations for the shot were finally completed after a good deal of groundwork. Once more I felt like I was a soldier in the army waiting to launch an attack at our general’s signal.

Bimalda’s calm voice announced.

‘Start sound!’

We met again at a dinner at the Ritz Hotel in Churchgate. The Filmfare magazine had organized a talent contest; I did not go for the contest but went to the dinner later. I had to borrow a Jodhpuri coat for the occasion from Tiger (the Nawab of Pataudi). Within a week of this meeting, I got a message from his company, Bimal Roy Productions, that he wished to meet me. I rejoiced at this news and literally flew to meet Bimalda at Mohan Studio.

Bimal Roy

Bimal Roy Memorial, All Rights Reserved © 2021

Designed & Developed by Trimoorti Creations.

Bimal Roy

All Rights Reserved © 2021

Designed & Developed by Trimoorti Creations.