The relentless media coverage about the pandemic we are stuck with was guaranteed to turn the toughest into a couch potato, an escapist. I confess to have succumbed.

Surfing through the daily cocktail mix of the tragic Sushant Singh case, the Rajasthan cabinet debacle followed by Congress CWC saga, I quickly settle for Netflix – to lunch with an eccentric English country GP DOC MARTIN – and have afternoon tea with KIMs – the neighbourhood shop owned by a crazy Korean family and as dinner time treat I have a rich selection of Hollywood-Bollywood classics . The Netflix serials, incidentally, discuss robust neighbourhood welfare. Despite these attractive distractions what nags me continuously is the question of current neighbourhood norms. I am forced to redefine who is a neighbour? Particularly in times of challenging emergency. I suddenly recall that neighbours and neighbourhood culture have frequently featured in Indian cinema. After all, Indian culture venerates guests, that includes neighbours. A sentiment expressed in the sayings atithi devo bhava- the Guest is God. And truly, not too long back, guests were considered extended family.

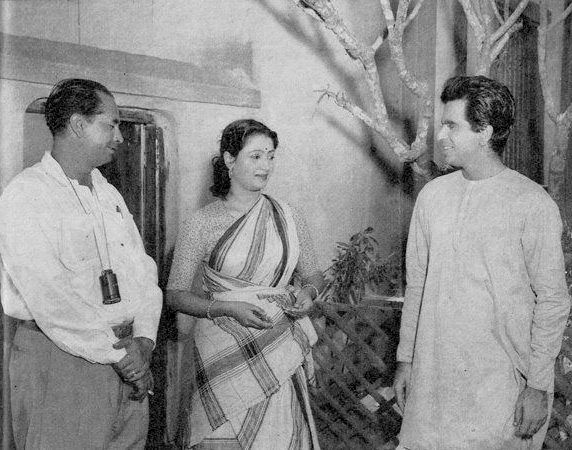

What comes to mind at once is that evergreen comedy PADOSAN with the wild bunch of comedians – Kishore Kumar, Sunil Dutt, Mehmood. A delightful Hindi remake of the comedy star Sabitri Chatterjee’s superhit Bangla 1952 film, PASHER BARI. Both films are girl meet boy next door romances. I have not seen PASHER BARI again, but remember it fondly. PADOSAN, the perennial charmer has endured. Not all neighbourhood sagas end happily ever after.

The 1941 V. Shantaram’s bilingual PADOSI & SHEJARI are iconic examples of what constructs ideal neighbourliness. Filmmaker Shantaram ostensibly set out to portray the saga of selfless friendship between a Muslim and his Hindu neighbour. The film’s intention was to project harmony, idealized amity through friendship in a society where communal disturbance frequently rears its ugly head. The Shantaram film stands out for its honest portrayals. To drive his point home Shantaram cast Gajanand Jagirdar, a noted Hindu actor, to play the character of the Muslim and Mazhar Khan to play the Hindu. A publicity stunt to be sure but till date the films retain their archival stature.

Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s PARINEETA, once again is a story about neighbours. How trust and friendship sour when money or politics enter the scene. In Shantaram’s film the good friends part when the Hindu man, who is the village Sarpanch, is accused by his Muslim neighbour of being prejudiced against the latter’s son.

In PARINEETA, Gurucharan and his wealthy landlord neighbour come to blows on the issue of unpaid debt. The landlord humiliates Gurucharan over money. Unknown to everyone, their children, Shekhar and Lalita, have fallen in love. Their romance thrives secretly. PARINEETA turns on its head because of the love angle. In Sarat babu’s most celebrated 50 page novella, DEVDAS, he created lovers who lived across the threshold. Devdas and Parvati’s love was doomed from start. The final nail on the coffin was Devdas’s indecisive nature. We can argue that in Sarat babu’s time there was no question of social distancing. On the contrary, social interaction, searching for love/romance within close quarters was a more viable option! It is well known that neighbours impact strongly in a rural society particularly in small towns. The opinion of neighbours, of the all powerful Panchayat, is of paramount importance that can make or break a family.

This brings me back again to the uneasy question – the role of neighbours, particularly in these challenging times. Is the familiar Biblical command “love thy neighbour” relevant or a gross overstatement? The idealist in me hopes it works.

I also hope the current situation would improve unneighbourly sentiments. I wonder again who are neighbours? Those who live next door? Guys we avoid at the landing or borrow sugar from? Today, when we have no choice but live with our neighbours has that equation altered?

In the urban setting social distancing is not a new phenomenon. It is a way of life where the Babu culture and class considerations segregates one strata from the other. We did not require a pandemic to reassert it. Agreed we should practice physical distancing as a safety measure. But to become a little island,? I find that unacceptable. In the caustic words of poet Robert Frost : “Good fences make good neighbours.” That seems to sum up the new normal – whatever that means.

The lockout I believe has opened newer channels of communication – of rediscovering neighbours. Our neighbours are the first point of contact in crises or during any unforeseen calamity This lockdown is a brilliant opportunity to rediscover ourselves, or find hidden talents within.

Here is a silver lining -the Dalai lama believes human relationships are founded on sharing food…the wise tradition of breaking bread, tasting salt. I agree entirely with the Dalai lama. My cousin cannot cook to save her life, her food comes from next door. Good friends Kerman and Mandira survive on tiffin their kind neighbours send. “it is like a nonstop picnic“ they chuckle. And my young Bengali neighbour, Sikha surprises me with tuck from her kitchen! Food for thought indeed.

I was delighted to read the opening lines of metaphysical English poet John Donne whose words affirm my vision of humanity:

“No man is an island

Entire of itself

Every man is a part of the continent

A part of the main”

Copy right @RINKI ROY BHATTACHARYA

September 5th, 2020

Close