Unknown to me, mother had invited a celebrated guest that particular night. And she extended her gracious invitation to us, me and husband Basu, for the special occasion. Dining with her was always a welcome affair. Her lavish hospitality and the gourmet repast each invitation promised was well known. So, I rarely passed up a meal with mother.

That night, however, she added something that struck me as odd.

“Come by 8.30.” She said before hanging up.

However, by the time we reached Godiwala Bungalow on Mount Mary Hill, it was well past nine. Her guests had arrived and comfortably seated in the elegant three piece Jacobian sofa set bought at a local auction.

Being an hour late, I felt terribly awkward enough to keep to some distance, wishing I could vanish into the wall. But looking towards us Maa began reciting her introductions.

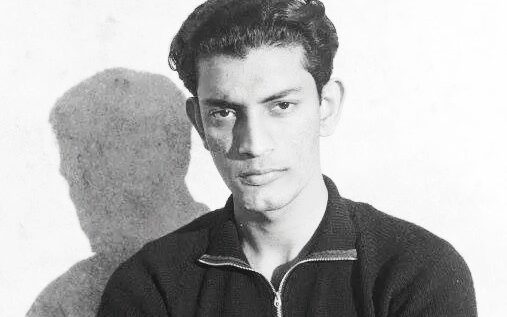

“Satyajit Babu this is my jamai(son in law) Basu – Basu Bhattacharya. He is a film maker …and my daughter, Rinki.”

From the corner of my eye, I saw that famous Leonine head turn 360 degrees and almost immediately his deep voice echoed in the vast Godiwala Bungalow hall:

“Rinki? The one who writes?” He said nonchalantly.

Without getting up from his seat, mother’s celebrated guest made this extraordinary pronouncement about me. The impact of which almost knocked me down, it did, in fact, knock me down instantly. Unbelievable! The world-renowned, busy director like Satyajit Ray had noticed my utterly modest writings! I don’t remember if I blushed but I was tongue tied with pride and self-worth all evening. Till date, his words gleam like secret gems lighting up my being.

After that, there was no looking back. Literally, none whatsoever. Emboldened by his generous recognition, I began to interact with Satyajit Ray who had become “Manikda”, on one pretext or another through letters. My letters were informal observations about his films, or film related. They amounted to little more than chit chatting. But Manikda never failed to answer back. From writing inconsequential letters, I graduated to making personal phone calls. Manikda himself received his telephone calls…how amazing that a man of his stature did not bother to engage a secretary? Or assistant? Every time I visited Calcutta, a visit to his Bishop Lefroy Road flat became the trip’s highpoint. Manikda seemed ready for an informal adda along with yummy homemade savories that his charming wife, Bijoya mashi, always served with tea.

In October 1984, I happened to be in Calcutta with an aspiring Norwegian writer, Mette Werner. Aware that for Mette meeting Ray, the celebrated filmmaker, was a treat she never dreamt of, I took an appointment. We were invited to go on the 31st. Manikda welcomed us at the appointed time. The large radio tuned to BBC world service, purred gently on one side. Within minutes of our arrival he turned up the volume of the radio and anxiously looked at us:

“How did you two come? Taxi? You better head home. Mrs. Gandhi has been shot. There will be a vicious backlash.”

By 11.45 A.M, BBC radio had confirmed Mrs. Gandhi’s death while the Indian news channels dragged their feet fearing fierce backlash. We left the lively adda, reluctantly, to return home. For the first time I realized that most Calcutta Taxi drivers are Sikhs, including the one we engaged. However, we reached home safely. By late afternoon on October 31st, the entire Bhowanipore area with its imposing Gurudwara, a Sikh dominated Calcutta neighbourhood, was ablaze. By evening, Calcutta streets were deserted. The traffic down to zero. The October ‘84 trip turned out to be a tragic yet memorable one.

Not only did I visit Manikda during my Calcutta trips, if he happened to be in Bombay for dubbing, or recording with Mangesh Desai, I would grab time to meet him at the Shalimar hotel which apparently was his favorite place here.

Much earlier, in 1976 I was in Calcutta. After settling at my sister’s Mandeville garden residence, I called Manikda to say I was in town and could I see him when convenient.

“So sorry Rinki,” he answered in his rich baritone voice. “I am busy shooting every day for my new film.” Perhaps he guessed my disappointment, as an afterthought, he quickly added: “But why don’t you come to the film set instead? In fact, come this afternoon. I am shooting with Richard. You would like that.”

Needless to say I was overjoyed for a rare opportunity to watch Manikda in action. I hastened late noon to the Technicians studio in Tollygunje. One of the first persons I saw hanging outside the floor was the young, unknown Victor Banerjee Manikda introduced with just two close ups in Shatranj Ke Khilari.

Inside the floor was the elaborate Oudh palace set meticulously created by art director Bansi Chandragupta. I was thrilled to see Sir Richard Attenborough appear in the role of General Outram with actress Veena (Wajid Ali Shah’s screen mother). The short scene that day was of the two trying to negotiate Wajid Ali’s abdication, rather, avoid it. I remember Tom Alter somewhere loitering in the background.

Incidentally, Munshi Premchand‘s short story by the same name was Manikda’s first Hindi language film in his repertoire. But he did go back to Premchand, directing India’s first color telefilm Sadgati in 1981 for Doordarshan… but did not return to big screen with a Hindi language film. Shatranj Ke Khilari, regrettably encountered extremely hostile opposition from the Bombay film industry. For example, the date for the film’s all India release was announced. I remember seeing a huge bill board at Worli looming opposite Haji Ali. To our utter dismay the banner was hastily pulled down and the film’s release indefinitely postponed. Industry rumours that the Bombay film industry did not welcome Ray’s entry was an open secret.

Being an ardent devotee of Manikda, I was boiling at the shabby manner in which the Bombay film industry treated him. As if he was about to upstage their positions. Wanting to know the inside picture, I called up producer Suresh Jindal. The untold story that emerged after our long-distance conversation was shamefully humiliating. I felt obliged to write an expose’. The Sunday magazine, edited those days by M.J.Akbar carried my expose’ as a lead story. Once the Shatranj story was out, I began to be targeted in the print media as a self styled Ray crusader! I ignored being trivialized for a while. But when it got viciously personal, SKM, the kind editor of Indian Express, invited me to respond in the editorial page. For me, defending Shatranj Ke Khilari was payback time. I admired Manikda openly, was privileged to be his protégé – I felt it was my ethical duty to expose the petty, mean, film politics against one of our greatest filmmakers. To be threatened that Satyajit Ray would take over the Hindi language cinema was a mindless conjecture. Through the challenging phase, Manikda maintained a dignified silence. But the experience left its bitter after-taste. Incidentally the Shatranj cover story was coming of age for me. I savoured both the success and notoriety that followed.

Interestingly, the dinner I mentioned earlier was when my mother hoped to discuss his directing a film for the Bimal Roy Productions. However, Manikda politely declined, admitting: “I am not comfortable with Hindi as you know.”

Ritwik Ghatak had proclaimed that Bimal Roy pulled “Bengali cinema out of the abyss.” He, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha virtually revered my father post Udayer Pathe. Manikda who was from the same generation, did not reveal his admiration. It was unexpectedly confirmed when I came across a rare nugget worth sharing today. In the Kolkata magazine interview by Jyotirmay Datta, Manikda casually mentioned :

“After Udayer Pathe Bimal Roy announced making Subodh Ghosh’s Fossil (Anjangadh). I read the story, wrote the screen play and went to meet Bimal Roy. He was apparently busy. I went back again. Though he recognized me as the cover illustrator of the Signet press, I returned disappointed.”

Although I enjoyed Manikda’s affection, or perhaps because of it I did not want to risk endangering our cherished bond. For several years therefore I did not share my much debated, indeed, the explosive 1984 Manushi interview. However, during one Calcutta visit, I left a copy impetuously, of Madhu Kishwar’s marathon interview. In which I laid bare the reasons for stepping out of my marriage. I even heard reports that my interview had raised uneasy question in the Parliament on the wide spread prevalence of spousal abuse.

Though I left the Manushi copy in a state of uncertainty, I was racked by pervasive anxiety about his reaction.

If his letter after reading the Manushi interview overwhelmed me, it felt like receiving a Nobel prize. He wrote: “The Manushi interview is exceptional in its boldness and honesty. And I don’t recall reading anything as candid in Indian Journal before…and I wholly endorse the spirit which prompted it”

I hesitate to quote the entire letter; afraid, it will seem like a vain boast. In fact Manushi wanted to publish it but Manikda disagreed.

Manikda’s letter is one of my few prized personal possessions. It is a living testament of his unfailing compassion, his understanding of a universally trivialized crime behind closed doors that has justly earned the term ‘domestic terrorism’.

I remain in Manikda’s debt for endorsing the spirit that compelled me to publicly speak against marital abuse. His support was conveyed privately, in a discreet manner- much like his films. Yet, it healed my broken spirit and restored my self-esteem that was being questioned daily by others who conspired to stay silent.

On Manikda’s birth anniversary, May 2nd, 2021, I pay this humble tribute to my distinguished mentor.

All rights reserved to the author.

Rinki Roy Bhattacharya

Original photographs taken by: Shambhu Shaha, Aloke Mitra, and, Dominique Faget